Over the course of my many classroom visits and teacher observations throughout my career, I am truly in awe of the master teacher. These teachers live and breathe all aspects of the teaching and learning process, from expert planning to delivery of engaging, differentiated lessons. They exude confidence and masterfully and effortlessly apply strategy knowledge and instructional pedagogy in teaching with differentiation for most needy students. Master teachers know how to use data to inform instructional decisions and apply core principles of intensive, systematic, direct instruction to accelerate learning.

Such expertise does not come easily or naturally to many, however. Advancing to the level of master teacher requires complete dedication and, in most cases, an insatiable appetite to better one’s skills and remain on a constant path of self-improvement and acquisition of new teaching tools. It is a career-long process well worth the effort when viewed through the prism of outstanding student outcomes.

So, where does a new special education teacher begin? In my view, one of the overarching issues is to determine one’s goal as an educator: prescriptive or pragmatic? Overcoming this “identity crisis” is the first step on the path to educator fulfillment and respect as a special education teacher. Are you going to take the role of prescribing the best available methods and materials to meet student needs or pragmatically teaching in lock-step with the curriculum?

I truly believe that most special educators would choose the former—a diagnostic/prescriptive role. However, the demands of covering content cannot be overlooked as our students require access to general curriculum as well as a strong program of remediation. In a former blog, I addressed the balancing act of meeting curriculum demands and remediation. The distinction here is the role and perspective of the teacher.

By way of example, I recently visited one of our high school programs for students primarily with emotional disabilities and behavioral disorders. The specific class was English 9. A few students were working independently, some students were working on the computer, and two students were working with the teacher. They all appeared engaged in their work. I positioned myself near the teacher and students in order to observe the lesson. For the entire period, the teacher worked only from the textbook. All prompts, dialogue, and questions were generated by the teacher’s manual. The teacher was systematically working through the grade-level text with the students, completing end-of-chapter questions and reading the vocabulary bolded in the margins as they went. It soon became apparent that the students were on vastly different reading levels, yet both needed to take and complete English 9. There was no introduction or pre-teaching of concepts or vocabulary, nor was there any evidence of use of guided or close reading strategies. It was a very pragmatic approach to the content with no indication whatsoever of “specialized instruction.”

I have no doubt that this young teacher was extremely invested in his students, but he lacked the skills required to prescribe what would be needed for this specific set of kids. By the end of the lesson, one student (the poorer reader of the two) had completely shut down, refusing to answer questions and physically covering his head with his hood. Given this pragmatic, cover-the-curriculum approach, this student might just as well have remained in his public school setting. He could have been equally as frustrated in that setting as he was in a separate special education program.

In watching this unfold, a number of questions crossed my mind:

- Has the teacher completed or reviewed any diagnostic assessments?

- Is the teacher aware of the strengths and weaknesses of this student?

- Is there an underlying learning disability driving the behavior?

- Is this the correct pairing of students or is there a better instructional match for the struggling reader?

- Where would I begin mentoring and coaching this young teacher to move him towards that of a diagnostic/prescriptive model?

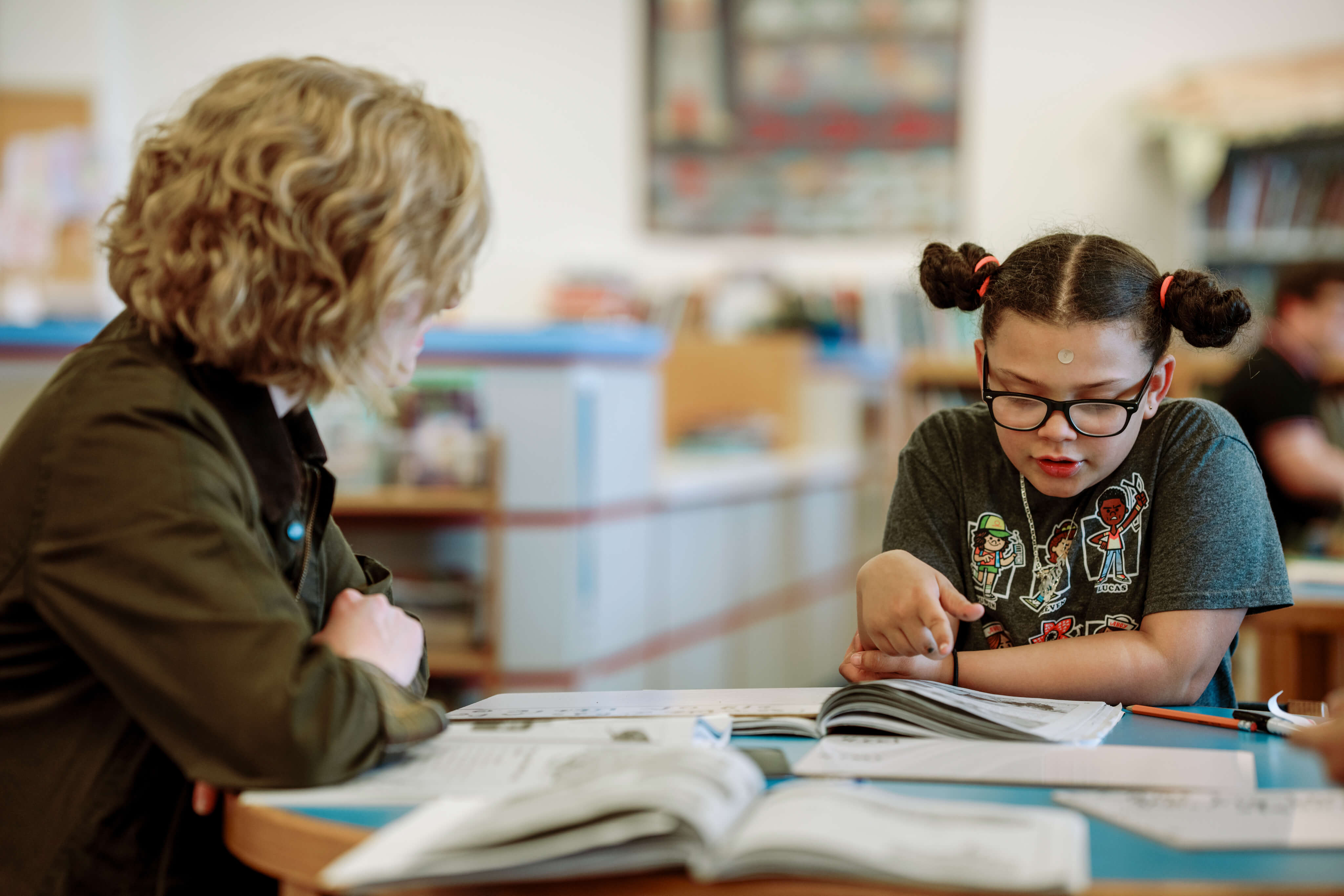

As luck would have it, I transitioned to another high school class (grade 11) on the same floor. This time, the teacher had three students for instruction while others worked independently or on the computer. It soon became apparent that I was in the presence of a master teacher. She, too, was working on an English lesson. Immediately, I saw evidence of advanced planning with differentiation with this group of students. She informed me that she makes decisions about which sections to cover based on her knowledge of state and local standards. The teacher espoused a “less is more approach” in selectively choosing the most salient aspects and skills targeted within individual units. That way, she explained, the students get much more out of the reading strategies and skills that she uses.

The teacher provided some background for me that led up to this day’s lesson. She knew she had three different reading levels within this group, ranging from second to fourth grade level. She obtained this information through diagnostic testing she had completed with her students. She went on to explain that this particular reading required some development of background knowledge, which she had done interactively on a Smart Board linked to a history website to provide context for the lesson.

The teacher also explained that she had spent some time developing academic vocabulary using a combination of morphological analysis and discussion to uncover the meaning. She informed me that they were doing a combined approach of listening to her read the story aloud, shared reading, and paired reading. For this lesson, she had copied a one-page excerpt from the short story for purposes of close reading. Her plan was to spend the next two to three days dissecting this passage for a variety of literary purposes: point of view, inference, and general understanding. She further explained that with each successive reading of the material, the students were more confident in their reading and their overall behavior was markedly improved.

The degree to which she fully understood her students was remarkable. Despite the great reading difficulty of this group, they were each successful due to her specialized instructional strategies. I was so proud of her, and it was a pleasure to be a part of this lesson.

Afterwards she and I discussed her exceptional skills and the need to mentor others. She already serves as head teacher and was looking forward to working with the young teacher I had previously observed.

I have attempted to draw a comparison between the role of true special education interventionist and pragmatist. In Part II of this blog, I will continue to explore the “identity crisis” findings for research-based programming for our most struggling students. Stay tuned!